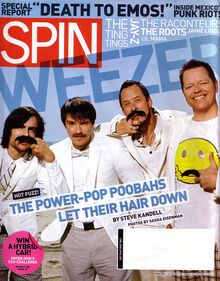

SPIN interview with Weezer - June 2008

| Print interview with Weezer, Luke Wood | |

|---|---|

Magazine cover | |

| Publication | SPIN |

| Published | June 2008 |

| Interviewer | Steve Kandell |

| Interviewee | Weezer, Luke Wood |

| Title | HECK ON WHEELS |

| Sub-title | THANKS TO A RENEWED SENSE OF FUN AND A CLUTCH OF GREAT ROCK SONGS ABOUT, UM, ROCK-NOT TO MENTION SOME GOOD OL' MARITAL RELATIONS - WEEZER ARE RIDING HIGH. NOT LITERALLY, OF COURSE. |

| Format | |

| Associated album | Weezer (The Red Album) |

| References | See where this article is referenced on Weezerpedia |

|

HECK ON WHEELS

THE GATE TO BOB DYLAN'S COMPOUND is wide open. Peering in, we can see an RV and a rusted '70s-vintage Volvo or maybe a Volkswagen. There's no telling how far back this dirt road goes or how much of this hilly Malibu coastline the hallowed property inhabits. We contemplate parlaying our leisurely scooter ride on this clear, mild April afternoon into a little leisurely trespassing. Or one of us does, anyway. "There's security cameras everywhere," Rivers Cuomo cautions warily. The 38-year-old Weezer frontman is wearing a blue zip-up hoodie, plaid shorts, and white tube socks pulled up to his knees. And, naturally, a helmet. "What's the worst that can happen?" I ask. "Your career would be over," he replies, grinning, then revs up his Vespa and veers around the block, deciding wisely, I now realize that this intrusion would be no way to treat a neighbor. I crane my neck for a last prying look and follow him back to his house. Much attention has been paid to Cuomo's peculiarly minimalist domestic needs-after ditching his material possessions in the summer of 2003, he lived in a converted garage in Hollywood with the windows blackened out, and at the peak of his stardom, he took up residence in a Harvard dorm to finish his bachelor's degree in English lit, When I last talked to him in late 2005, he was two and a half years into a two-year vow of celibacy, wondering aloud whether being in a rock band was conducive to achieving his real dream of having a family. Now he owns sweet scooters and a house in a tony Point Dume enclave somewhere berween Dylan's and Mel Gibson's, while the surest proof that his celibacy has ended, 11-month-old daughter Mia, is off visiting Grandma with Kyoko, Cuomo's wife of two years. And, although it was in doubt for a while there, Cuomo is still very much in a rock band. In fact, Weezer's eponymous sixth full-length-helpfully dubbed the "Red Album" to distinguish it from 1994's beloved debut "Blue Album" and 2001's beliked "Green Album," but consciously suggesting those records' breeziness-is virtually a concept album about how fuckin' rad it is to be in a rock band. Weezer formed at the height of grunge, appropriating its woe-is-me lyrics and big guitars and indie's understated geek-chic, adding a winking sense of humor too often lacking in both genres. A generation later, a lot has changed. A lot has not. With two modest bedrooms and a pool surrounded by childproof fencing, Cuomo's ranch house, enviable as it is, does not necessarily look like it belongs to a man who's sold more than ten million albums. Which is to say, it does look like it belongs to Rivers Cuomo. That's his Subaru Legacy in the driveway. Even at his most indulgent, he will not allow himself any more than he needs. This neighborhood feels like magic to me. We saw something like 30 houses; this was our favorite," he says. As much as people have tried to fit Cuomo into the eccentric pop genius/Brian Wilson role - and certainly his disposition toward oversharing details about his sex life (or lack thereof) has fed into that - he's merely a proud suburban dad showing off his backyard. "It's not too big; modern houses are really big. We don't want to clean that much." The first thought is that Cuomo must be joking - surely it's occurred to him that he has the means to get a little help with the dusting and mopping. But, colossal ham that he may be, Cuomo is never exactly joking. His recent YouTube clips inviting fans to help him write a song aren't a goof, but rather evidence of the former autocrat's newfound openness to collaboration. Atop his lip rests a bushy mustache that men under 40 generally cultivate either to win a bet or after losing one. But he grew it when Mia was born as a tribute to his own father, who sports one in all of Cuomo's old baby photos. Malibu was not the Cuomos' only option; they were also checking out homes in Connecticut, just down the street from where his parents lived. In the wake of the bad vibes surrounding the last Weezer effort, 2005's Make Believe, Cuomo's ambivalence about continuing the band nearly drove him back East for good. But he downplays that ambivalence now, shrugging it off as if the fate of one of the most enduring and commercially steady acts in rock wasn't hanging in the balance. "I don't remember what I was thinking," he says. "Maybe I didn't know if I was going to get back into music and just wanted to settle down." He nods his head and squints a bit, as if trying to conjure a hazy memory from decades ago. "That must have been what I was thinking." To a man, the members of Weezer acknowledge that the period surrounding the relatively maudlin, navel-gazing Make Believe was a tough one and that the album suffered as a result, albeit not commercially - it still sold 1.2 million copies in the U.S. and spawned their most successful single, "Beverly Hills." Cuomo was back at Harvard, while the other three were left to interpret his demos on their own, and beyond that, his recent immersion in stringent vipassana meditation didn't necessarily lend itself to the rigors of recording and promoting a rock album. But each is quick to dismiss the idea that the band, which earlier had endured a tenuous hiatus between 1996's Pinkerton and the Green Album, was truly in danger of breaking up. On this point they are insistent and vigorously on-message, if perhaps selectively amnesiac. "The biggest misconception is that we don't get along," says bassist Scott Shriner, a tea-scented toothpick nestled next to a gold-capped front tooth. "Horrible misconception." Strolling through the Autry Museum of the American West in Griffith Park, Shriner stops at a glass case displaying guns from the 19th century and recalls that when he moved to Los Angeles from Toledo in 1990 not long after a two-year stint in the Marines, he packed his bass amp, his coffee maker, and a shotgun. ("I was from Ohio; I thought L.A. was gonna be dangerous.") Although he's still technically the new guy, Shriner has been in Weezer for three of their six albums and seven of their 14 years. He is just over the hump now, a unique vantage point from which to observe the band's dynamic, even as his role within it solidifies and grows. At 42, he's the oldest member, and given that the closest Shriner had come to success previously was playing bass for Vanilla Ice during the erstwhile rapper's nü-metal phase, he may have the most at stake in the group's well-being. Which is why he greets with a wince the mere mention of a magazine article from three years ago that spelled out in no uncertain terms (and in his own words) how the band did not, in fact, get along. "Yeah, I was having a bad day," he says, smiling, eager to change the subject. "I feel like saying anything about all that is just giving it power, you know? It just seems so irrelevant now, like a different lifetime." Instead, Shriner accentuates the positive, recounting the feel-good listening parties - with cupcakes! - in late 2006 where Cuomo first presented his new demos to the band and explaining how their four wildly disparate personalities and musical tastes actually serve to improve the group's chemistry. And how that tension is what makes Weezer "the greatest band that ever lived." "It's a four-way yin and yang," he says. "If you take away the guy who listens to Gary Numan or the guy who listens to Dylan all day or the guy who listens to Japanese pop or the guy who listens to Mastodon, then it won't sound the same." For all the platitudes about how bands are like families and even families go through rough patches, etc., even at the outset, Weezer were never about four pals piling into the van for kicks; they were careerist and commercially ambitious even in 1993, when careerism and commercial ambition were not in vogue. "It's the 'music business,' not the 'music fun," says guitarist Brian Bell, 39, who joined Weezer midway through the recording of the first album and who doesn't appear to have aged a day since. Perched in the sunroom of his Encino ranch house wearing a charcoal pinstripe blazer with a tear in the right armpit, the band's lone remaining bachelor has seen enough low points and weird left turns to know that Make Believe was not really going to be the end - "It's not the swan song Rivers wanted," he says - and tried to assure Shriner of as much as the tour was winding down. Even so, it was clear to all that for the band to continue, they would have to change how they operated on a fundamental level. "I think we're the only band in the history of rock with a mission statement and a constitution," Bell says. "The Constitution of the United States of Weezer was drafted over a year ago as a way of making sure we stay true to our goals, and it kept us focused in a way we'd never been before. We have to prove to ourselves that we're still valid and that rock music is still valid." No one will divulge any specific tenets of this sacred parchment, but a major one seems to concern the division of labor. While Cuomo has always been the band's de facto leader (and he admits he is publicly perceived as "the guy who wears glasses and is nerdy and whines a lot and is a control freak"), he was more than ready to share the burden. Everyone contributed songs and switched instruments, and the new album features two tracks that were neither written nor sung by Rivers Cuomo: Bell's "Thought I Knew" and drummer Pat Wilson's "Automatic." A third, Cuomo's uncharacteristically creepy "Cold, Dark World," has Shriner on lead vocals. This newfound equanimity was put to an early test: Rick Rubin, who'd produced Make Believe, once again offered his services. But after tracking only a handful of songs in early 2007, Rubin disappeared for reasons no one seems entirely clear on, nor particularly bitter about. "We didn't necessarily want to stop working with him," says Bell. "More like he stopped working with us." (Rubin declined a request to be interviewed for this story.) The unexpected change of plans did force the band to adapt on the fly, so they decamped to a theater, the Malibu Performing Arts Center near Cuomo's house, to record on their own from July to September. A third session lasting ten days in February with Dublin-based producer Jacknife Lee, fresh off the recent R.E.M. album, proved so successful that Weezer have already locked him up for record number seven - very, very tentatively due for release in November 2009. The members of Weezer, and certainly their ardent fan base, are quick to categorize each album as a reaction to what came previously-Make Believe was meant to correct the self-indulgence of 2002's Maladroit, which was meant to be more experimental than the meat-and-potatoes Green Album, which was meant to reassure fans after the quirkiness of Pinkerton, which was meant to shake things up after the blockbuster debut. But put the band's discography on shuffle for a casual listen, and the songs are all more similar than not. This hasn't stopped people from heralding the Red Album as a return to übercatchy form. It's this consistency that's both allowed for Weezer's continued success and made them easy to take for granted in a fickle, flavor-of-the-half-hour marketplace. "I honestly don't think that's a problem," says Luke Wood, who worked in Geffen's marketing department during the Blue Album period and is now, as a top Interscope executive, the band's most important champion. "They don't chase trends, and I hope they get rewarded for that. We hear a great album with big hit songs, and how often do you get that? It's honey for bees." "I would say we're probably more popular now than ever," says the Buffalo-bred Wilson, 39, who lives with his wife and their two kids in Canyon Lake, an hour south of L.A., "at least based on ticket sales. We're neither here nor there; we have our own universe. We exist between matter and antimatter. Perhaps I'm naive, but I think it's simple: If you just rock, people want the rock." As he's been married for nearly all of Weezer's lifespan, Wilson's relative ease in mixing domestic tranquility with the insanity of life on the road is what ultimately proved to Cuomo that he might be able to do the same. "I never identified with the idea of 'I wanna be in a band because I want chicks.' The whole lifestyle part of it, I don't get at all," Wilson says. "I've never even seen cocaine. Ever." If the men of Weezer consider themselves impervious to seismic zeitgeist shifts, certainly some supporting evidence can be seen at Spin's cover shoot on Venice Beach, where a quartet of tween girls (and their moms) excitedly take photos of the band. The Red Album's first two singles, "Pork and Beans" and "Troublemaker," effortlessly distill nose-thumbing teenage angst into undeniably hooky choruses. That they were crafted by a bunch of middle-age dudes in such a way that sounds honest, rather than pandering, is Weezer's greatest trick. "In its purest form, rock is about the struggles of adolescence, and there's something about rock as an idea that illustrates that period of someone's life," says Interscope's Wood. "I feel like Rivers hasn't lost any sense of wonder about music or about its oppositional nature." As much as Cuomo considers himself removed from L.A.'s entertainment factory, he may actually be its most accomplished Method actor: In order to properly relate to the misfit teenager, he must be a misfit teenager. IT WAS ALWAYS WEIRD being a kid and singing along to these Kiss lyrics about womanizing and having no idea what they were talking about. Then listening to Slayer and not being into Satan myself." If the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ever presents an exhibit re-creating Rivers Cuomo's childhood bedroom, it might not look markedly different from the approximately eight-by 12-foot guest cottage in his backyard. Above the door hangs a wooden sign his older brother made in ninth grade: PETER'S ROOM. (Cuomo, who was raised on an ashram in Connecticut, went by the name Peter Kitts, after his stepfather, during his teenage years.) His old Kiss records are mounted on the walls in protective plastic sleeves, as is Odyssey of Iska, the LP by jazz saxophonist Wayne Shorter on which his father, Frank, played drums. His dad's old kit fills a third of the room. A few guitars hang from hooks; Cuomo takes down a particularly battered Fender. "This was my first guitar," he says, handing it over for inspection. A Kiss logo and an inverted cross are gouged into the head and the neck, respectively. This guitar, given to him some 25 years ago, has been set on fire repeatedly, but of all its battle scars, the rust-colored smudges above the pickups stand out. "I would bite my fingers when concentrating really hard," he says. "That's blood." Loose-leaf binders containing every song he's ever written, organized by year, line shelves, but he's particularly proud of his Nirvana notebook, in which he dissects their songs into patterns and formulas. For Cuomo, pop is always a riddle to be solved, something he idealizes even as he breaks it down to its mathematical essence. And his fascination with personal nostalgia is not relegated to fandom; Cuomo is in the midst of an self-excavation, mining artifacts from his past and interviewing people he knew more than 15 years ago. Some of the old demos and snapshots were included in last year's Alone: The Home Recordings of Rivers Cuomo, but the real bounty will come with the memoir he's shopping to publishers, which focuses on his life between 1992 to 1994. As he grows comfortable, finally, with his own stature and status, it also becomes clearer that of all the tribulations Cuomo has wrestled with in his songs and otherwise-spiritual unfulfillment, a bum leg, a broken home, sexual identity-perhaps none tortures him more than a lone tonsorial choice made 15 years ago. "The whole Weezer aesthetic was a negation of everything I'd stood for," Cuomo says, now sitting in his den. A map of the world covers one wall; pillows are clustered in the corner for meditation. "I was a passionate metalhead. I told my mom I was never going to cut my hair, and then right before the Blue Album photos were taken, I did and was a completely new person." He opens a Tupperware bin and wistfully sifts through a tangle of studded wristbands and belts and dingy bandannas from his glam days. "I was playing guitar in a band that sounded like Queensrÿche, then I made this sudden about-face that made a lot of people mad. I had a sinking feeling that it was so against my grain, but as it turns out, the repressed instincts from those times have surfaced in different ways." Those ways have never been more apparent than on the Red Album - no fewer than four of its ten songs tackle the subject of rockness explicitly and self-reflexively. An artist who categorizes his default authorial voice as "emo complainer guy," Rivers Cuomo is fully embracing and even tweaking his quixotic public image for lyrical fodder. Rollicking album-opener "Troublemaker" boasts, "I'm gonna be a star and people will crane necks/To get a glimpse of me and see if I am having sex," while "Pork and Beans" wonders aloud whether enlisting Timbaland might help make the song a hit. "Heart Songs" shows its love in more obvious fashion, rattling off a laundry list of inspirational pop songs that misattributes the remake of "I Think We're Alone Now" to Debbie Gibson, rather than Tiffany. ("It was a mistake, but I decided to leave it in there," Cuomo says. "I hope they don't take it the wrong way - maybe they had problems like that back in the '80s, with people not being able to distinguish them.") But the album's centerpiece is the cheekily grandiose "Greatest Man (Variations on a Shaker Hymn)," which tackles rock megalomania in the only way that makes sense: by exploding the sonic kitchen-sinkism of "Bohemian Rhapsody" and "A Quick One, While He's Away" to its logical, po-mo extreme. (It's hard to imagine the celibate, self-flagellating Cuomo of Make Believe delivering couplets like "You try to play cool like you just don't care/But soon I'll be playin' in your underwear" or "I got the money, and I got the fame/And you got the hots to ride on my plane.") Yet when asked if he thinks these songs are indeed reflective of a new outlook on his rock stardom, or on rock stardom in general, the man who spent, like, six pages deconstructing "Rape Me" seems surprised that anyone would give the context of his lyrics that sort of consideration. He pauses carefully and thoughtfully before answering even the simplest of questions, but he chews on this one an extra while. "I don't know," he finally says. "From a creativity standpoint, I wanted to change who I am in the song.... Being a rock star has meant many different things over the last 14 years. This is not what I was thinking of when I was in bed at night dreaming about being in Kiss; this is chill. In my 20s, I remember thinking, "Man, I'm a rock star, I should be living the life.' I'd push myself, but it's just not in my constitution. Maybe that's why we're still around." WEEZER GATHER, along with their manager, Dan Field, at a photo studio in Venice, staring at four potential Red Album covers on a laptop screen. A final selection was due yesterday, but they're not even close, so they're soliciting opinions from anyone they can find. The photos were taken in October, before the sessions with Jacknife Lee, "so we wouldn't have to make the decision last minute," Cuomo deadpans. If the band does have a control freak in it, it'd be good if he stepped forward now. Bell prefers the version with the band sitting, his legs stretching way into the foreground. Cuomo (and, as it turns out, the label) prefers the one in which he sports a black cowboy hat, a western shirt, and what appears to be a beer gut. A third features the four members frolicking in the ocean. The fourth has the guys clad in white surrounded by an angelic burst of light and is, as Cuomo says, "the one people seem to hate the least." For all the talk of shifting industry paradigms, Weezer revel in their conventional approach. And while the band and the label were definitely at loggerheads when Cuomo circumvented the brass to mail out advance copies of Maladroit himself or to let fans select the track list, they're simpatico now. They need each other. "You know, Trent Reznor says he's doing it without a label now, but he still has a bunch of people working for him," says Bell. "I feel lucky that there's a company that believes in our music and will promote it, and I believe that gives us an advantage. You need someone to have a plan. And all the young people I know in bands, they still want to get signed. It gives a sense of worth, it's something your parents can understand." "The whole indie way of seeing things felt like a cliché to us at that point," Cuomo says of the band's early days. "We were like, 'No, we're going to sign to a major, we're gonna do this as corporately as possible.' That, to us, felt rebellious." Nor does Cuomo feel intimidated by a landscape that's changed drastically since. "I bet we could do it all over again - start a new band, hide our identities, figure out the right moves, and make it all over again. Sounds like a dare." The band's immediate plans after the album's June release are typically murky. Bell thinks he's heard rumblings of shows in Japan later in the summer. But if collabo-crazy Cuomo's vision for the next Weezer tour comes to fruition, they won't be the ones doing the rocking out. "I'd love to do really small shows, a few hundred people seated in the round, and the stage is loaded with all kinds of instruments and furniture and people hang out onstage and join in," Cuomo says. "Like a hootenanny. It's gonna be nuts." But isn't he chomping at the bit to get out there and further indulge his inner rock star? The roaring, adoring crowd? The lights and the hubbub? All that crap? Cuomo pauses. And then shrugs. "I'm not much of a bit-chomper," he says. "But I'm sure it's gonna be killer." |

Gallery

-

Features

-

Page one

-

Page two

-

Page three

-

Page four

-

Page five

-

Page six

-

Page seven

| More Weezer interviews from 2008: | |

|---|---|

| Other band member interviews from this year: | |

| Other material from SPIN: | |

| Other archives: | |